Games

Cards appeared in Spain and Italy about 1370, but they probably came from Egypt. They began to spread throughout Europe and came into England around 1460. By the time of Elizabeth’s reign, gambling was a common sport. Cards were not played only by the upper class. Many of the lower classes had access to playing cards. The card suits tended to change over time. The first Italian and Spanish decks had the same suits: Swords, Batons/ Clubs, Cups, and Coins. The suits often changed from country to country. England probably followed the Latin version, initially using cards imported from Spain but later relying on more convenient supplies from France.

In Orleans, France (1408) an inventory of the Duke and Duchess of Orleans lists “ung jeu de quartes sarrasines and unes quartes de Lombardie” (one pack of Saracen cards and one cards of Lombard, Dummet 42). During the Elizabethan era in England cards were block printed, unwaxed, bore a single image in the center of card, and had blank backs. The English used the French system of suits (clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades) while German and Swiss cards favored shields, acorns, flowers, and bells. Italian cards featured the latin suits of coins, cups, batons, and swords.

Two of the most popular games in Italy, where tarocchi (tarot or tarock) or trionfi (trump) decks were used, were scartino and imperiali. These decks had 78 cards; four suits numbered one through ten, a page, a knight, a queen, and a king, twenty-one tarots which acted as trumps, and a fool which acted as an ‘excuse’ or a special trump. The tarot deck was not originally used for divination, but for a trick-taking game that is one of the oldest card games known. The numbers on the trumps are the only thing that matter, the images have no effect on the game itself and as such could be altered at the engravers choice (Ortalli 24).

Most of the decks that have survived use the French Suit: Spades, Hearts, Clubs, and Diamonds. Yet even before Elizabeth I had begun to reign, the number of cards had been standardized to 52 cards per deck. Interestingly, the lowest court subject in England was called the “knave.” The lowest court card was therefore called the knave until later when the term “Jack” became more common.

SOURCES

Archaeologia by Daines Barrington, 1787

The Game of Tarot by Michael Dummett, 1980

The Prince and Playing Cards:The Este Family by Gherardo Ortalli, 1996

In Orleans, France (1408) an inventory of the Duke and Duchess of Orleans lists “ung jeu de quartes sarrasines and unes quartes de Lombardie” (one pack of Saracen cards and one cards of Lombard, Dummet 42). During the Elizabethan era in England cards were block printed, unwaxed, bore a single image in the center of card, and had blank backs. The English used the French system of suits (clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades) while German and Swiss cards favored shields, acorns, flowers, and bells. Italian cards featured the latin suits of coins, cups, batons, and swords.

Two of the most popular games in Italy, where tarocchi (tarot or tarock) or trionfi (trump) decks were used, were scartino and imperiali. These decks had 78 cards; four suits numbered one through ten, a page, a knight, a queen, and a king, twenty-one tarots which acted as trumps, and a fool which acted as an ‘excuse’ or a special trump. The tarot deck was not originally used for divination, but for a trick-taking game that is one of the oldest card games known. The numbers on the trumps are the only thing that matter, the images have no effect on the game itself and as such could be altered at the engravers choice (Ortalli 24).

Most of the decks that have survived use the French Suit: Spades, Hearts, Clubs, and Diamonds. Yet even before Elizabeth I had begun to reign, the number of cards had been standardized to 52 cards per deck. Interestingly, the lowest court subject in England was called the “knave.” The lowest court card was therefore called the knave until later when the term “Jack” became more common.

SOURCES

Archaeologia by Daines Barrington, 1787

The Game of Tarot by Michael Dummett, 1980

The Prince and Playing Cards:The Este Family by Gherardo Ortalli, 1996

Game of Ruff (Italy, 1522) -

Draughts (Checkers, Europe, 1300s) -

Needs: standard deck of cards, four players. Aim: to score nine points. Players agree on a stake. Deal 12 cards to each player and turn up remaining top card on deck to determine trump suit. The player with the Ace of the trump suit declares “I have the honour”, and scores a point for each of the four honour cards they hold (Ace, King, Queen, Jack). The player to the left of the dealer leads and all players follow suit. Aces high or trumps takes the suit. If they cannot follow suit, they may play any card. The winner of the trick leads. The players gain one point for every trick taken. If there is no winner, another stake is required and another hand played.

In draughts the object of the game is to capture your opponent’s game pieces by making diagonal jumps over them. The game is a descendant of the Egyptian game of alquerque, which was played on a five-by-five-point board with twelve interlocking “L” shaped pieces. The game was played at court and in the taverns of England by all classes. The Earl of Leicester had a set made with pieces of crystal and silver and a board bearing his family’s heraldic crest. This game was also known as jeu force in France, for a game where a player must take and opponent’s piece whenever possible (as does alquerque).

The object of the game is to capture or immobilize your opponent’s twelve pieces. A capture is made by a piece (man) jumping over an enemy piece and landing on a vacant square immediately beyond. If the capturing piece can continue to leap over the other enemy pieces they are also captured and removed from the board. When a piece finally comes to rest the move is finished.

If an uncrowned piece reaches the opponents back line it becomes a king. Crowning ends a move. After crowning a king can move diagonally backwards and forwards one square at a time, and captures by a standard jump. There may be several kings on the board at a time.

In Italian Draughts, a number of rules apply to captures (Bell 73):

SOURCES

Sports and Games of the Renaissance (2004) by Andrew Leibs.

Bingo then moved to France where it became known as “Le Lotto”. Bingo is still today played in France every Saturday in a similar fashion as we play nowadays. It is played with playing cards, tokens, and numbers called aloud.

Scartino

A card game called Scartino, the favorite of the Este family, is one of which we hear much from a brief period around 1500: there are over a dozen references to it between 1492 and 1517. We have no idea how Scartino was played, although it appears to have demanded a special type of pack; for instance, Lodovico il Moro wrote in 1496 to Cardinal Ippolito d’Este complaining that the latter had not sent him the carte de scartino that he had promised, and there are other references to orders for packs of Scartino cards. The game seems to have originated from Ferrara: it was a favourite game both of Beatrice d’Este, wife of Lodovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, and of Isabella d’Este, wife of Francesco Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua. Isabella also loved to use her impresa, or device, embroidered on her robes and painted on the playing cards. The name Scartino is presumably connected with the verb scartare, ‘to discard’, and games are often named after their most characteristic or novel feature. It is therefore a possibility that this was a trick-taking game in which a new practice was introduced, namely that the dealer took some extra cards and discarded a corresponding number. If so, it could be that it was from Scartino that this practice was taken over into Tarocco games, in which it had been previously unknown, and that Scartino, after its short-lived popularity, died out, having made a lasting contribution to card play. This, of course, is the merest guess: Scartino may not have been a trick-taking game at all, but, say, one in which the winner was the player who first contrived to get rid of all his cards after the fashion of a stops game.

Many wonder if it was appropriate for women to play cards. We know the Isabella and her sister-in-law Elisaetta were known to sit in the afternoon and “together they sang French songs and read the latest romances, or played scartino, their favourite game at cards, in the pleasant rooms which Francesco had prepared for his bride on the first floor of the Castello, near the Sala degh Sposi. Together they rode and walked in the park and boated on the crystal waters of the lake, or took excursions to the neighbouring villas of Porto and Marmirolo.”

A letter of August 1493 quoted by Malaguzzi-Valeri and by Luzio and Renier appears to imply that Scartino was a three-handed game. The earliest reference is from 1492; one is from 1509, one from 1517, and all the rest from the 1490′s. Several concern the obtaining or ordering of packs of Scartino cards (para de carte da scartino or para de scartini), which appear all to have come from Ferrara; what was special about these cards there is no way of telling. It is just conceivable that Scartino was itself a particular type of Tarot game, and that these were therefore Tarot packs of a special type; but, unless they were very special, it does not seem very likely that Lodovico Sforza should have been having to obtain Tarot packs from elsewhere. Most of the references are about games of Scartino being played.

Draughts (per Master Damiano Bellini) “was played in France, England, and the Spanish Marches before 1500. In the Italian version, the 8×8 board is placed so that the double black corner is on the player’s left instead of right. Each player has twelve pieces set up on the black squares of the first three rows in front of him. The pieces move only on the black squares and black has the first move. The pieces move diagonally forwards one square at a time and may not move backwards.

If an uncrowned piece reaches the opponents back line it becomes a king. Crowning ends a move. After crowning a king can move diagonally backwards and forwards one square at a time, and captures by a standard jump. There may be several kings on the board at a time.

In Italian Draughts, a number of rules apply to captures (Bell 73):

- A player had to take when possible or lose the game

- A man (piece) could not take a king

- If he had a choice of capture he was forced to take the greater number

- If he had a choice of capture he was forced to take the greater number

- If this number were equal (each option containing a king) when there are two or more options, then he must capture wherever the king occurs first. This rule was known in Italy as ‘il piu col piu’ (‘the greater to the greater’)

Sports and Games of the Renaissance (2004) by Andrew Leibs.

Maw was developed in 16th Century Ireland and was a favorite in the British Isles. The object of maw is to win three tricks or prevent other players from doing so. It can be played with anywhere from 2 to 10 players. A pot is decided and the winner gets the pot. If there is no winner, a second hand is played and the first to win three tricks gets the pot. Each player is dealt give cards from a 52-card deck. The top card of the remaining cards is flipped up to determine the trump. Regardless of suit, the trump cards rank; five, jack, ace of hearts, ace of trump, king queen. If the trump suit is red the remaining cards rank from 10 down to 2, and vice-versa if the trump suit it black. Non-trump cards of the same color rank the same as trump cards. The person to the left of the dealer leads, playing one card. The other players must follow suit or play a trump. If a player can do neither, she may play any card. A player can hold the five and jack of the trump or the ace of hearts if they choose, but lesser trumps must be played if the player can not follow suit.

Bingo’s Origins in Italy

Most agree that Bingo was first played in an Italian lottery called “Lo Giuoco del Lotto D’Italia”. The game appears on record around 1530 in the late Renaissance Italy. It is said to have developed from a game known as “Lotto” which in Italian means “destiny or fate”. It was first played in a period during a corrupt election that needed a fresh way to select a leader. Numbers were chosen randomly and the person who had that specific number would then be the new leader purely by fate.Bingo then moved to France where it became known as “Le Lotto”. Bingo is still today played in France every Saturday in a similar fashion as we play nowadays. It is played with playing cards, tokens, and numbers called aloud.

Scartino

A card game called Scartino, the favorite of the Este family, is one of which we hear much from a brief period around 1500: there are over a dozen references to it between 1492 and 1517. We have no idea how Scartino was played, although it appears to have demanded a special type of pack; for instance, Lodovico il Moro wrote in 1496 to Cardinal Ippolito d’Este complaining that the latter had not sent him the carte de scartino that he had promised, and there are other references to orders for packs of Scartino cards. The game seems to have originated from Ferrara: it was a favourite game both of Beatrice d’Este, wife of Lodovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, and of Isabella d’Este, wife of Francesco Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua. Isabella also loved to use her impresa, or device, embroidered on her robes and painted on the playing cards. The name Scartino is presumably connected with the verb scartare, ‘to discard’, and games are often named after their most characteristic or novel feature. It is therefore a possibility that this was a trick-taking game in which a new practice was introduced, namely that the dealer took some extra cards and discarded a corresponding number. If so, it could be that it was from Scartino that this practice was taken over into Tarocco games, in which it had been previously unknown, and that Scartino, after its short-lived popularity, died out, having made a lasting contribution to card play. This, of course, is the merest guess: Scartino may not have been a trick-taking game at all, but, say, one in which the winner was the player who first contrived to get rid of all his cards after the fashion of a stops game.

Many wonder if it was appropriate for women to play cards. We know the Isabella and her sister-in-law Elisaetta were known to sit in the afternoon and “together they sang French songs and read the latest romances, or played scartino, their favourite game at cards, in the pleasant rooms which Francesco had prepared for his bride on the first floor of the Castello, near the Sala degh Sposi. Together they rode and walked in the park and boated on the crystal waters of the lake, or took excursions to the neighbouring villas of Porto and Marmirolo.”

A letter of August 1493 quoted by Malaguzzi-Valeri and by Luzio and Renier appears to imply that Scartino was a three-handed game. The earliest reference is from 1492; one is from 1509, one from 1517, and all the rest from the 1490′s. Several concern the obtaining or ordering of packs of Scartino cards (para de carte da scartino or para de scartini), which appear all to have come from Ferrara; what was special about these cards there is no way of telling. It is just conceivable that Scartino was itself a particular type of Tarot game, and that these were therefore Tarot packs of a special type; but, unless they were very special, it does not seem very likely that Lodovico Sforza should have been having to obtain Tarot packs from elsewhere. Most of the references are about games of Scartino being played.

We learn from Isabella d’Este’s brother-in-law letter to the Marquis in 1503 that playing cards was her regular pastime: “Yesterday I went with this illustrious Madonna and Signor Federico to the school of Messer Franceso, whose scholars recited a fine comedy exceedingly well. It was a very pretty sight, and pleased us all highly. Afterwards we drove as usual to take the air in the town, and returned to the Castello about five o’clock; and Madonna (Isabella) sat down to cards to spend the evening after her usual custom, and played till after eight. Then she rose from the table and told me that she would not come to supper as she felt pains, and went to her room, and we sat down to table, and I supped in the Castello. And before we had finished, the said Madonna gave birth to a little girl, and although we greatly desired a boy, yet we must be content with what is given us.”

SOURCES

Cartwright, Julia. Marchioness of Mantua

F. Malaguzzi-Valeri, La carte di Locovico il Moro, vol. 1, Milan, 1913, p. 575;

A. Venturi, ‘Relazioni artistiche tra le corti di Milano e Ferrara nel secolo XV’, Archivio Storico Lombardo, anno XII (pp. 255-280), 1885, p. 254;

A. Luzio and R. Renier, Mantova e Urbino, Turin and Rome, 1893, pp. 63-5, especially fn. 3, p. 63;

A. Luzio and R. Renier, ‘Delle relazioni di Isabella d’Este Gonzaga con Lodivico e Beatrice Sforza’, Archivio Storico Lombardo, anno XVII (pp. 74-119, 346-99, 619-74), 1890, p. 368, fn. 1, and pp. 379-80;

A Luzio I precettori d’Esabella d’Este, p. 22;

G. Bertoni, ‘Tarocchi versificati’ in Poesie, leggende, costumanze del medioevo, Modena 1917, p. 219;

Diario Ferrarese of 1499 in Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, vol. 24, p. 376.

Playing Cards

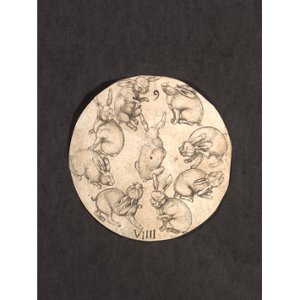

Master P W of Cologne’s pack of seventy-two rounded playing cards is generally believed to be his last work in the medium of engraving. This card, the 9 of hares, is 6.3 cm in diameter and was made circa 1500 in Koln, Germany. It comes from a pack of seventy-two round playing cards and is unique in having five suits, rather than the customary four: roses, columbines, carnations, parrots and hares. The images on the cards depict plants and animals based on the study of nature, rather than of model books as previous engravers of cards had done (VAM).

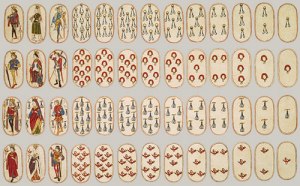

An early use of the woodblock for printing was for making playing cards. Surviving examples of printed cards date to as early as about 1420. This sheet is thought to have been made by an artist called F. Durand in Rouen or Lyons in the first half of the 16th century. It has not yet been cut, showing the way in which cards were made for economy, printed many to a sheet and cut at a later stage. The high quality of detail and careful application of hand-colouring suggests that this pack was intended for a well-off client. It is an uncut sheet of playing cards, containing eight subjects, four Kings and four Queens bearing titles of legendary and historical personages (VAM).

Cartwright, Julia. Marchioness of Mantua

F. Malaguzzi-Valeri, La carte di Locovico il Moro, vol. 1, Milan, 1913, p. 575;

A. Venturi, ‘Relazioni artistiche tra le corti di Milano e Ferrara nel secolo XV’, Archivio Storico Lombardo, anno XII (pp. 255-280), 1885, p. 254;

A. Luzio and R. Renier, Mantova e Urbino, Turin and Rome, 1893, pp. 63-5, especially fn. 3, p. 63;

A. Luzio and R. Renier, ‘Delle relazioni di Isabella d’Este Gonzaga con Lodivico e Beatrice Sforza’, Archivio Storico Lombardo, anno XVII (pp. 74-119, 346-99, 619-74), 1890, p. 368, fn. 1, and pp. 379-80;

A Luzio I precettori d’Esabella d’Este, p. 22;

G. Bertoni, ‘Tarocchi versificati’ in Poesie, leggende, costumanze del medioevo, Modena 1917, p. 219;

Diario Ferrarese of 1499 in Muratori, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, vol. 24, p. 376.

Master P W of Cologne’s pack of seventy-two rounded playing cards is generally believed to be his last work in the medium of engraving. This card, the 9 of hares, is 6.3 cm in diameter and was made circa 1500 in Koln, Germany. It comes from a pack of seventy-two round playing cards and is unique in having five suits, rather than the customary four: roses, columbines, carnations, parrots and hares. The images on the cards depict plants and animals based on the study of nature, rather than of model books as previous engravers of cards had done (VAM).

An early use of the woodblock for printing was for making playing cards. Surviving examples of printed cards date to as early as about 1420. This sheet is thought to have been made by an artist called F. Durand in Rouen or Lyons in the first half of the 16th century. It has not yet been cut, showing the way in which cards were made for economy, printed many to a sheet and cut at a later stage. The high quality of detail and careful application of hand-colouring suggests that this pack was intended for a well-off client. It is an uncut sheet of playing cards, containing eight subjects, four Kings and four Queens bearing titles of legendary and historical personages (VAM).

SOURCES

Victoria and Albert Museum

Victoria and Albert Museum

[Source: La Bella Donna]

No comments:

Post a Comment